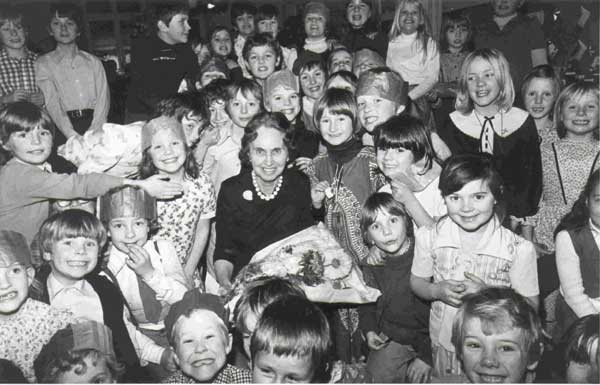

Daphne Hanlon

Daphne Hanlon

continues her memories of Kelling School

when she was Head mistress

The authorities realised we couldn't go on like that, so they decided to take the children of over eleven, and send

them to another school. Meanwhile the older girls all went into Holt on a Tuesday for cookery which they didn't like, and they never wanted to go!

One boy, I won't say his name but he was a lovely boy, he had chickens and rabbits, and he said to me 'On Friday I go to market', I said 'Oh, do you?' He said 'I got to sell my rabbits'. He did very well; he made money and I accepted the fact. Nowadays you wouldn't be allowed to, would you? But he was doing actually more good there than he was at school. He was fourteen, not much good on the literary side but extremely good on the maths side.I had a secretary for one day a week and there was nowhere to put her, so she sat on the edge of my table. There was no telephone of course, not for ages, it was a marvellous thing when we got the telephone, and we shouldn't have had one if it hadn.t been for Mrs Watson-Cooke who was a councillor. She visited us and said 'Oh, you must have one, my dear!'. She was a wonderful woman, she just went straight through like that. The phone had to be in the class room, obviously. Sometimes when it used to ring I.d pick it up and say very crossly 'Sorry, I can't talk to you now, I'm teaching'. The Education Office people thought they could ring up any time.

Mrs. Watson-Cooke

I was always terribly keen on drama, and every year each class did a play, and we did most elaborate things really. I remember one with a dragon in it. We never had one person not in the play. As I say, the parents didn't trust me with their children when I first came, but in no time at all they were being wonderful; I only had to  say to them 'We'll have a fair, what will you do?' and they'd all come to sit in my room in my house and decide what stall they'd have. They all worked so well together, they were wonderful, and that money that was made on the fair was used to take the children away. The youth hostelling would be a week away, all over the country. It was my class, so it was ages 8-11, and my husband used to go as well to be with the boys in the youth hostels. We used Mr Sanders' first coach and he was superb. We went to the Lakes, and Derbyshire, and we went to Somerset. We worked on all aspects of where we were going, so they knew all about what they were going to see.

say to them 'We'll have a fair, what will you do?' and they'd all come to sit in my room in my house and decide what stall they'd have. They all worked so well together, they were wonderful, and that money that was made on the fair was used to take the children away. The youth hostelling would be a week away, all over the country. It was my class, so it was ages 8-11, and my husband used to go as well to be with the boys in the youth hostels. We used Mr Sanders' first coach and he was superb. We went to the Lakes, and Derbyshire, and we went to Somerset. We worked on all aspects of where we were going, so they knew all about what they were going to see.

In the thirty years I was there, I taught the people's children who had been my first children! I have very happy memories.